Everyday IP: The history of sneakers

Some call them "trainers" or "runners;" others call them "tennis shoes," "basketball shoes" or even "gutties." But across much of the world, people know exactly what you are talking about when you say "sneakers."

These seemingly straightforward shoes have a massive social footprint extending far beyond sports and into music, movies, TV, social media and other pop culture realms. This gives sneakers immense value not only in commercial terms but also as Intellectual Property (IP) assets. Brands with lucrative sneaker-related trademarks and patents work overtime to protect them. We examine how and why everyday footwear sprang to dizzying heights.

Origins and etymology

The earliest "sneakers" debuted in 1876, made by the England-based New Liverpool Rubber Company, and were immediately notable as the world's first rubber-soled shoes. They were often called "beach shoes" (referencing a place you would likely see them worn) or "plimsolls" (in connection to the Plimsoll line where a fully-laden ship's hull meets the water's surface). Elsewhere, these early sneakers and their like were called tennis shoes.

The term "sneakers" originates in the United States, but its derivation was incorrectly documented until recently. Because the word appeared in a 1917 Keds advertisement, many thought that marketer Henry McKinney had coined it. In 2010, researcher Andrew Newman found an 1887 Boston Journal of Education article that used "sneakers" with regard to children sneaking up on teachers thanks to their shoes' soft soles.

Growing popularity

From the 1890s to the 1930s, sneaker designs saw some notable developments. Reebok's early success in the closing years of the 19th century (back when it was J.W. Foster and Sons) stemmed from its leather running shoes, which used metal spikes to give wearers a better grip. In Germany, Adolf "Adi" Dassler and his older brother Rudolf began making running and football shoes in the 1920s. Both types were made of leather, but the football variant used studs, which provided more grip and control on grass than spikes.

Adi and Rudolf Dassler set up their first shoe factory in Herzogenaurach in the early 1920s. To this day, the reason for their eventual falling out remains a mystery, even for the rival companies they went on to found. (Image credit: Wikipedia)

Other inventions of the time included Converse's 1922 basketball sneakers, featuring rubber soles and high-top canvas uppers. These gave more support to the ankle and heel (for that time) than other non-leather versions. It is unclear if any one individual devised these innovations — but it certainly was not semi-pro basketball player Chuck Taylor.

All the same, Taylor's brand ambassadorship as a traveling salesman inspired Converse to connect him to its IP. Putting his impressive skills on display, he promoted the shoes at basketball seminars across the United States, sending eager spectators in droves to sponsoring local retailers. Realizing his far-reaching popularity, the company added Taylor's signature to its five-point star logo in 1932. That symbol, and the largely unchanged high-top Converse sneaker, are still well recognized to this day.

Meanwhile, in 1936, the world watched in awe as U.S. running star Jesse Owens dominated at the Olympics in Berlin. It did not go unnoticed that the sneakers he wore en route to four gold medals were created by the Dassler brothers.

War and IPs

The Second World War curtailed sneaker production and innovation for even the biggest brands. Many manufacturers converted factory operations to rubber production, but Converse enjoyed the benefits of U.S. Army contracts. The Dasslers, meanwhile, found their shoe factory forced to produce "Panzerschreck" ("tank terror") anti-tank weapons in 1944. After the war ended, their association with Owens' triumphs meant that the occupying U.S. servicemen were enthusiastic about getting their hands on (and feet into) a pair of Dassler sneakers. The company quickly resurged as sales exploded.

The Dasslers also understood the value of IP – perhaps more so than any sneaker designers to date. However, after long-simmering tensions ended their joint shoe business, the brothers established rival factories in their hometown of Herzogenaurach. Rudolf was the first to commence operations, launching his "Ruda" company in January 1948. Adi started a competing "Adidas" venture in August of the following year. On October 1, 1948, Rudolf registered "PUMA" at the German Patent and Trademark Office (DPMA) and renamed his company. Ever since, the rivaling sibling companies have remained headquartered in the same town.

In 1952, Adi Dassler convinced Karhu Sports, a Finnish sportswear business, to sell him its "three stripes" logo, allegedly for two bottles of whisky and the modern equivalent of €1,600! That symbol has been synonymous with Adidas since then and, consequently, a massively valuable trademark. By contrast, Puma's leaping-cat silhouette, while itself highly successful, cannot boast of the same level of renown.

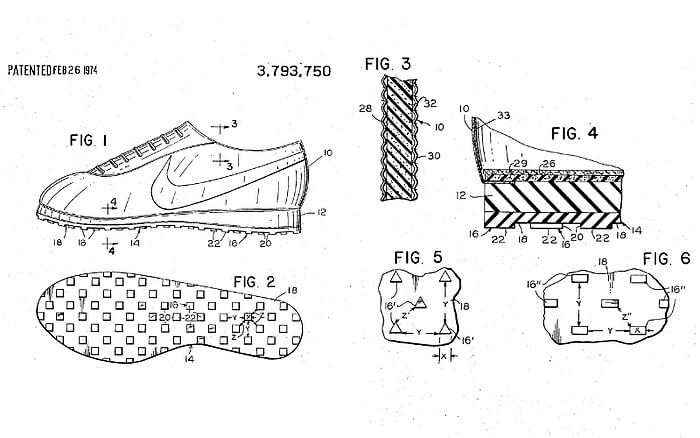

Nike co-founder Bill Bowerman created the sole for his lightweight design using his wife's waffle iron. The resulting trend pattern was reminiscent of footprints left by astronauts on the moon, inspiring the nickname "Moon Shoes." (Image credit: Espacenet)

As the years went on, maturing demand saw various sneaker companies emerge. The 1960s brought the creation of Nike and Vans, brands that eventually became hugely popular. But their success did not come about overnight. Nike started as the nondescript-sounding Blue Ribbon Sports (BRS), not adopting its current name and ubiquitous "swoosh" logo until 1971 and not gaining trademark protection for the design for another three years.

On the other hand, Vans only truly took off in the mid-1970s, as skateboarders and BMX bikers adopted the sneakers for the "sticky" traction of their soles. The company's famous "Off The Wall" slogan and logo debuted at this time. Testament to their "sticking power," they remain heavily associated with skater, BMX and punk-rock subcultures.

In this same decade, Nike founders Phil Knight and Bill Bowerman focused on developments that are now common across numerous athletic and casual sneaker brands such as air-cushioned soles.

The endorsement surge and roots of sneaker culture

Football legend Pelé's preference for Puma and tennis star Stan Smith's Adidas kicks were fashion highlights of the 1970s. But the 1980s turned endorsements into a phenomenon: Famous athletes across multiple sports helped the logos of sneaker brands permeate culture like never before — becoming some of the world's best-known trademarks in the process.

National Basketball Association (NBA) prodigy, Michael Jordan, became a Nike sponsor in 1984. The combination of Jordan's stratospheric fame, Nike's innovations and groundbreaking commercials by film director Spike Lee made the Air Jordan sneaker line an enduring favorite of fans and players. Today, Air Jordan is one of the most popular sportswear brands, and the "Jumpman" logo of Jordan's silhouette is still a slam-dunk, contributing to the player's netting of over $1 billion USD from the lasting partnership.

Adidas had a strong presence in the 1980s, most notably through its longtime soccer connections and an established partnership with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. However, their biggest milestone of that decade was outside sports: Hip-hop group Run-DMC became the first musical artist to earn a shoe endorsement with the classic single "My Adidas" in 1986. Meanwhile, Vans and Converse sneakers (especially the latter's high-tops) were being widely adopted by fans of punk, heavy metal and grunge music around this time. This imprinted Converse's IP into multiple brand-skeptical subcultures at just the right time — namely, when their function as basketball shoes had been thoroughly eclipsed by Nike and Adidas.

Chuck Taylor might not have designed the sneakers that bear his signature, but his indefatigable promotion of the young brand secured his place in storefronts around the world. (Image credit: lenscap50 - stock.adobe.com)

But not all was going Nike's way at the time. It was not until the 1988 debut of its "Just do it" slogan, that the company set itself on the path to true industry dominance.

The especially close association of product and IP seen in the sneaker industry has given rise to a resale industry worth about $6 billion USD, as fans endeavor to find limited-edition or vintage pairs of top brands. The rarest sneakers are often in non-standard designs or "colorways," but their all-important trademark elements remain unaltered.

Anti-infringement in the sneaker industry

We have examined the Adidas vs. Shoe Branding Europe case more than once on this blog: first regarding the EU General Court's interpretation of acquired distinctiveness and the requirement for proof of use and later as part of a broader discussion on European shoemakers' trademarking efforts.

That case is, however, but one example of the lengths sneaker companies go to in order to protect their IP. At any given time, the industry's biggest global players juggle multiple high-stakes lawsuits among each other and smaller enterprises:

- Adidas just lost a trademark dispute with designer Thom Browne and has a separate counterfeit claim in U.S. federal court.

- Nike has two notable trademark infringement cases pending. The first case pertains to non-fungible tokens (NFTs) that allegedly use Nike branding without permission; the second is a more straightforward trademark infringement.

- Even more remarkably, the Nike-Adidas dispute over the former's Flyknit technology — which began with Nike suing Adidas in a German court in 2012 and continued through multiple U.S. federal districts for years — finally concluded with an apparent settlement in August 2022. On the other hand, Adidas' suit against Nike over its "smart sneaker" patented technology shows no signs of resolving soon.

- Vans filed two major IP lawsuits in 2022 that are awaiting resolution. The second, more recent case is against U.S. retail giant Walmart, which Vans alleges is a repeat infringer of its IP.

Top-brand sneakers have assumed a secondary role as status symbols, making them a prime target for counterfeiters and knock-offs.

Given the tremendous legal costs involved, these litigations are anything but frivolous. In the world of fashion and footwear, registered marks for trade dresses and brand names are the beating heart of market value. Properly renewed, these IP assets offer longer-lasting protection than design rights (or, where applicable, patents) since copyrights do not apply to garments and apparel.

The profitability of the footwear market contributes to the urgency with which sneaker brands fight against infringement — and the persistence with which infringers and counterfeiters break the law. Non-athletic (or "athleisure") sneakers generated approximately $73 billion in worldwide revenue during 2022, with athletic footwear accounting for an additional $50 billion. Yet the counterfeit sneaker market in 2021 was estimated to be worth up to $450 billion, some five and a half times the legitimate market at that time.

In the grand narrative of IP, sneakers are a standout example of value enhancement. Hence, appropriate registration and enforcement strategies are vital for keeping your IP rights on track. The experts at Dennemeyer go the extra mile to ensure your trademarks, patents and design are fully protected, so you and your brand can keep on running.

Filed in

IP infringement disputes abound in the film industry but some are more dramatic than others. Explore the unusual IP cases spawned from prominent movies.