Everyday IP: The big picture of the small screen - innovations behind television

Even with the seemingly inescapable presence of smartphones and computers in life today, television still has an impact that sets it apart from other entertainment media. Unsurprisingly, the history of such a revolutionary invention abounds with stories of Intellectual Property (IP) rights and disputes.

And it is the invention of the television set itself that we concern ourselves with, rather than broadcasting's context as an artistic, entertainment, journalistic and educational format. The complex tapestry of innovations and patents behind this technological stalwart might make you pause for reflection the next time you pass an electronics storefront or reach for your voice-activated remote control.

All in a spin: TV's mechanical roots

The first appearance of the word "television" is in an unassuming, fairly succinct paper written in 1900 by Russian scientist Constantin Perskyi. As it was prepared for the International Electrical Congress of the World's Fair in Paris, Perskyi wrote in French. When devising a shorthand for his method of "reproducing at a distance luminous radiations representing the image of an object by means of electricity," the scientist chose a portmanteau of the French words "télé" (far) and "vision" (sight). To this day, French people use "télé" as slang for TV, while their neighbors in the United Kingdom still frequently speak of "telly."

Of course, the technology Perskyi was positing did not then exist other than in the most rudimentary forms. For instance, as early as 1862, there was Giovanni Caselli's "pantelegraph," which allowed the transmission of "facsimile" images by telegraph. Though a precursor technology to analog television and fax machines, the pantelegraph was a towering iron monster unfit for all but the most spacious office or living room.

Since Caselli's pantelegraph required a very accurate timing pendulum, the entire apparatus stood around 2 meters (6 feet 7 inches) tall. Visually and technically impressive, Emperor Napoleon III was so taken by the machine on May 10, 1860, that he set aside a telegraph line between Amiens and Paris for Caselli's experiments. (Detail of a 1933 replica. Image credit: Wikipedia)

The closest anyone came to a more practical solution during the 19th century was Paul Nipkow, with his "Elektrisches Teleskop" (electronic telescope). Images would be focused by a lens onto a spinning disk (eventually named for its inventor) marked with holes in a spiral pattern. As the disk rotated, each hole would allow a "slice" of the image to pass through to a selenium light sensor, permitting an electrical signal to be captured and sent. Although Nipkow received an Imperial German patent in 1885, the system was hampered by the fact that a similar disk spinning at the exact same rate was needed to reproduce the image for the viewer. Hence, by the time Nipkow witnessed a television for the first time in 1928 in Berlin, purely electronic methods were about to surge ahead.

De Forest and his patent wars

An early obstacle faced by television pioneers was the issue of transmission. As mentioned, Caselli's pantelegraph relied on telegraph lines, hindering uptake. So U.S. inventor Lee de Forest's patent for the "grid Audion" for detecting and amplifying radio waves in 1907 seemed to be a game-changer. But the filament and vacuum tube design — eventually pivotal to TV technology — was accused of infringing on John Ambrose Fleming's valve patent as owned by Guglielmo Marconi's company. The litigation ended in 1943 when the U.S. Supreme Court automatically invalidated the Fleming valve patent for an improper disclaimer.

Meanwhile, de Forest spent years embroiled in a bitter patent dispute with Edwin Armstrong over a different tube signal amplifier. De Forest eventually won due to the first-to-invent principle; the United States only became a first-inventor-to-file jurisdiction in 2013. But his public reputation was that of a "sore winner," as he continually lambasted Armstrong even after his rival's 1954 death.

Farnsworth vs. Zworykin

Last year, we summarized Philo T. Farnsworth's story as a young inventor who reshaped the world. But if the history of television displays any recurring themes, it is the inevitability of patent litigation, to which not even the fresh-faced Farnsworth was immune. As a 14-year-old living in rural Idaho, he came up with the idea of a non-mechanical television that created images by firing electrons onto a glass screen. Lacking the resources to develop his invention, he expressed the idea in diagrams drawn for his chemistry teacher.

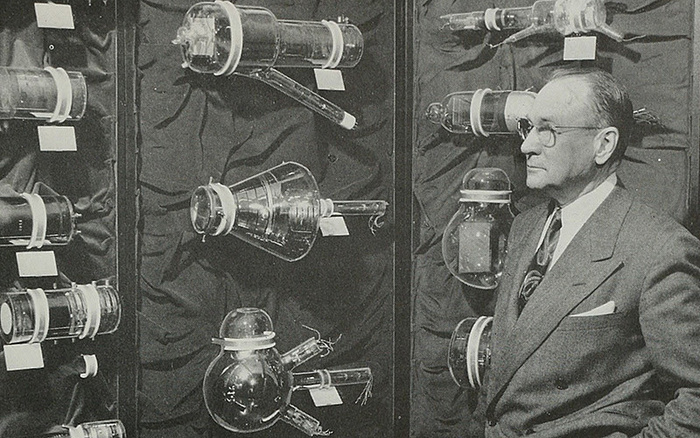

Though perhaps unjustly overlooked in favor of a "farmboy prodigy," Vladimir Zworykin made many contributions to the early history of television. His pioneering work on video camera tubes, such as the "iconoscope," set the stage for ever greater fidelity in image capture. (Source: Radio Age magazine, Radio Corporation of America, New York, Vol. 13, No. 4, October 1954, p. 27. via Wikipedia)

Those illustrations would later prove crucial. Recognizing early on the importance of the cathode ray tube to image reproduction, Farnsworth demonstrated the world's first all-electronic television to his lab assistants in 1927 (at age 21) and had patented it by 1930.

However, Vladimir Zworykin was to be the basis for a patent infringement lawsuit filed by Radio Corporation of America (RCA). The Russian-American inventor had filed a patent in 1923 for his similar TV system, prompting RCA, who owned the IP rights, to claim priority over Farnsworth's design. But because of the first-to-invent standard, Farnsworth had the edge with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), relying on his teenage diagrams as evidence to counter RCA. The telecommunications giant dragged out the affair until 1939, when it agreed to pay Farnsworth's company a sum of $1 million USD over 10 years – on top of licensing fees.

Unfortunately, the Second World War shut down television manufacturing, severely limiting Farnsworth's ability to earn royalties before the expiration of his patent. Despite working feverishly and holding more than 300 patents, including for a nuclear fusion reactor you can build at home(!), Farnsworth spent much of his adult life bedeviled by financial troubles and depression. Meanwhile, Zworykin went on to contribute to the development of infrared imaging technologies and the electron microscope, continuing in the field of medical engineering after his retirement from RCA in 1954.

From color to HDTV (and beyond)

John Logie Baird patented a color TV system in 1928 based on the Nipkow disk concept. In 1934, the United Kingdom's Electric and Musical Industries (EMI) Limited received a patent grant for the TV camera technology dubbed Emitron. Two years later, the company gained another patent for an improved version, creating what is generally considered the earliest high-definition television (HDTV) system — albeit not much like the HDTV we know today. However, also in 1936, the Hungarian inventor Kálmán Tihanyi conceived of a flat-screen TV with a plasma display.

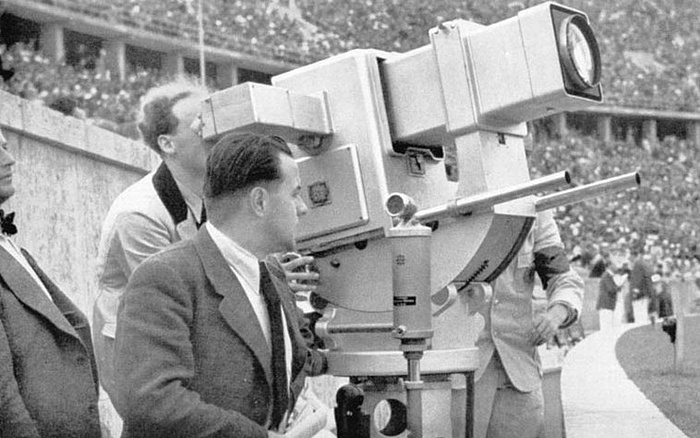

The "Olympic Cannon" in operation at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin. Though the Second World War would heavily curtail television broadcasting, cameras such as those developed by German engineer Emil Mechau from Zworykin's iconoscope technology would go on to redefine entertainment. (Image credit: Wikipedia)

There were several significant changes to the way television was filmed and broadcast during the years of the Farnsworth-Zworykin rivalry and more than a few between then and the late 20th century. But for much of that time, TV sets — even as they grew smaller, became colorized and started receiving cable, digital or satellite broadcasts — relied on cathode ray tubes similar to those developed by Farnsworth and Zworykin.

Flat-screen sets, mostly using plasma display panel (PDP) or liquid-crystal display (LCD) technology, only began to take over in the late 1990s and early years of the 21st century. Their development cannot be easily traced to any single inventor as they were the product of fierce competition between electronics manufacturers, including Panasonic, Sony, Sharp, Epson, Fujitsu and Philips. That said, modern LCD technology can be traced back to the patents of inventors Richard Williams, Wolfgang Helfrich and Martin Schadt from the 1960s and 70s. In the end, LCDs eventually supplanted PDPs because of falling costs, lower energy consumption and lighter weights.

Japan launched the world's first official HDTV service in 1989 in a now-discontinued analog format. Digital television — and, even more notably, digital HDTV — did not emerge until the late 1990s, with the transition from analog broadcasting to digital methods beginning around the turn of the millennium.

Today's "smart TV" sets allow users to browse the internet, access video streaming services, play video games without a console, shop and much more. But as advanced as they are, they still owe their existence to an imaginative American teenager, a studious Russian-American scientist and many more innovators — not to mention the patent protection they obtained (and fought over).

Filed in

IP infringement disputes abound in the film industry but some are more dramatic than others. Explore the unusual IP cases spawned from prominent movies.