Everyday IP: Cycling through time

The bicycle appears simple at a glance, generally consisting of two wheels, a frame, foot pedals, a drivetrain, a seat, handlebars and (hopefully) brakes. But this is somewhat deceptive. You have only to pick up a pencil and draw one without looking at a reference picture to realize there is a lot more to this seemingly straightforward vehicle.

Bicycles are so familiar to us that it is easy to forget they are a comparatively recent invention. Much like automobiles, the history of bicycles is full of Intellectual Property (IP) disputes that, at times, draw in historians as well as patent claimants. In our time, bicycles are a staple of society, valued as much as a method of transportation and thrilling spectator sport as for their contribution to sustainability, public health and good old-fashioned fun.

A much-disputed origin story

Several people have been incorrectly credited with inventing the bicycle, most famously Leonardo da Vinci and a Scottish blacksmith named Kirkpatrick Macmillan. Neither made these claims himself, with Macmillan's friends and relatives posthumously asserting he had invented a two-wheeled, pedal-powered bicycle in 1839. Without any concrete evidence or contemporaneous reports, these contentions are viewed dubiously at best.

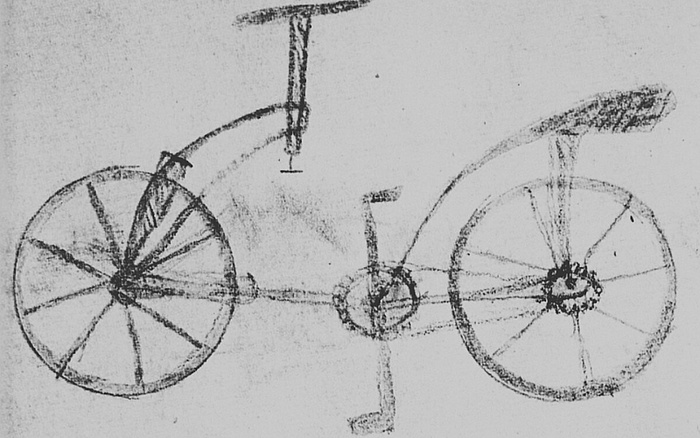

The da Vinci story is fascinating, though: In 1974, Italian scholar Augusto Marinoni, widely considered a da Vinci expert, announced he had found a rudimentary bicycle design in the Renaissance inventor's Codex Atlanticus. The discovery, however, fell apart under scrutiny from German historian Hans-Erhard Lessing. He considered the rather crude drawing a forgery, snuck into the Codex by a monk working to restore it. Why? Possibly boredom, possibly Italian national pride. No one today can know for sure. In fairness to Marinoni, the scholar said a da Vinci student poorly representing his teacher's work actually drew the bike, and his overall reputation did not seriously falter from what most considered an error of excess enthusiasm. Yet Marinoni spent his remaining years certain the sketch was authentic.

The uncanny shape of the "da Vinci" bicycle has been attributed to the artist's tracing of pre-existing lines visible from the other side of the paper. But uncharacteristic coarseness aside, what helped strengthen the sketch's plausibility was the fact da Vinci did conceptualize a metal chain with bearings. (Image source: Wikipedia Commons)

So who invented the bicycle?

When it comes to reliable proof of innovation, there is little that can compete with a patent grant. In 1817, German civil servant and former baron Karl von Drais patented his two-wheeled, foot-powered, fully steerable vehicle, a world-first in personal transportation.

Drais named his vehicle the Laufmaschine ("running machine"), the French called it the draisienne and numerous names were used in English, including draisine, velocipede and hobby horse. Because most early bicycles were considered playthings of the wealthy, some even called them "dandy horses." (Ironically, Drais' inspiration for the invention is believed to have been partly an 1815 crop shortage that seriously affected horses.)

If anyone could be called the "father of the bicycle," it would be Karl von Drais. But the appreciation of his peers was short-lived, as numerous cities, including London and New York, banned his vehicle as a nuisance to pedestrians. Also, despite patenting his Laufmaschine in France and Germany, Drais could not defend against imitations in other countries. (There was no PCT nationalization back then, after all.) Rivals like England's Denis Johnson could copy and patent Drais' invention, albeit while improving it with larger wheels for enhanced stability.

Nevertheless, Johnson's success was equally unsustainable as he faced the same problems as Drais. Over the next few decades, velocipedes trended away from two-wheeled designs, opting for three or four wheels instead, being less affected by uneven and rough terrain. Many of these were powered by pedals or treadles and could theoretically go faster, but they were also heavy and impractical. And although Philipp Moritz Fischer of Schweinfurt, Germany, invented the first pedal crank for a two-wheeled bicycle in 1853, he did not patent or even publicize his accomplishment.

Boneshakers, penny-farthings and safety bicycles

In the early 1860s, French blacksmith Pierre Michaux invented a bicycle with pedals affixed to the front wheel with the help of his son, Ernest. The elder Michaux did not patent his invention but had sufficient financial backing and resources to mass-produce the bicycle, starting a multi-year craze.

The bike's primary problem was comfort, as the iron-strip tires and oversized wheels made for a bumpy ride — hence its nickname, the "boneshaker." Around the same time, another French inventor, Pierre Lallement, developed a pedal-powered bike with a slightly smaller front wheel and did patent his creation in 1866 after emigrating to the United States. But the Franco-Prussian war soon ended the boneshaker era in France. Meanwhile, the avarice of carriage firm owner Calvin Witty — who bought Lallement's patent and charged an exorbitant licensing fee of $10 per bicycle sold (about $190 USD today) — stifled the nascent market in the United States.

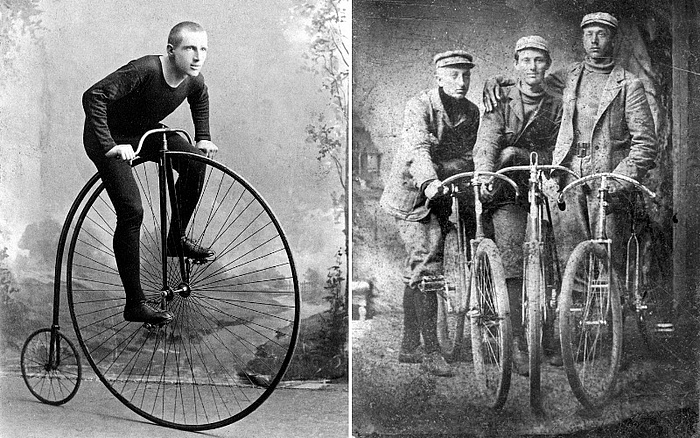

The benefit of a huge propelling wheel was that it multiplied the distance moved by the rider's feet: A slow revolution from the pedals would translate to a very high speed at the rim. Thankfully, the later implementation of chain-driven sprockets made this treacherous technology obsolete.

Yet, when most people imagine antique bicycles, it is the outlandish-looking penny-farthing that springs to mind. Emerging in 1869, Eugène Meyer first designed a bike with a massive front and tiny back wheel, and it quickly became popular among Parisian bicycle racers due to the front wheel's tremendous speed. Unfortunately, while Meyer is recognized by historians today, he did not patent his new bike (only the wheels' new steel spokes), making room for British inventor James Starley to adapt his design and enjoy some financial success. It was in England that the penny-farthing, or "bicycle" as it was known at the time, briefly took off. Starley's own contribution to the technology was significant, though, as he patented the tangential arrangement of spokes that is still the standard in bicycles today.

But more than any other design, it was the "safety bicycle" that truly brought bikes into the mainstream in 1885. Invented by John Kemp Starley (nephew to James), this model used wheels of equal size, an improved rear-wheel drivetrain for better propulsion and a diamond-shaped frame. So called to distinguish it from the precarious "ordinary bicycles," the younger Starley's machine spurred widespread imitation and further innovation — such as John Dunlop's pneumatic tire in 1893, which gave bikes a much smoother riding experience.

The rise of the safety bike triggered a short-lived boom in the United States. But this oversaturation coincided with the development of public transit networks in urban areas, and the market collapsed spectacularly. From the early to middle 20th century, bikes were most popular in Europe, as could be expected from the provenance of the inventors mentioned above.

Diversification in the modern era

Even with two World Wars hampering production at times, the half-century from 1900-1950 saw the emergence of a flurry of developments in cycling technology:

- Multi-speed shifting (thanks to the derailleur)

- Vastly improved braking systems

- A plethora of frame styles of varying weights and materials

- The recumbent design (allowing riders to sit all the way down while pedaling)

- Quick-release wheel hubs

This is not a complete list – and patents for folding designs and suspension appeared even earlier – but it demonstrates how quickly bicycles (and their underlying components) changed.

The layout of the modern bicycle has changed surprisingly little in over a century. Nevertheless, no component has been left untouched by the spirit of innovation. From ergonomic saddles to electric lights and advanced brakes, even the most "basic" of machines holds plentiful promise for generations of inventors.

Perhaps even more notable is how the prevalence of cycling has grown by leaps and bounds during the 20th and early 21st centuries. Once seen largely as a novel but awkward means of transportation, bicycles are now a practical and carbon-neutral solution in economic powerhouses and developing countries alike. That is why there are more than one billion bicycles currently in circulation, with about 250 million sold in 2021 alone.

The purpose of bicycling has also considerably expanded. Transportation and leisure outweigh other purposes, but racing is incredibly popular as well: growing from a mostly European niche activity to a competitive sport enjoyed worldwide. The Tour de France alone attracts millions of views every year, and the other two "Triple Crown" events — the Giro d'Italia and UCI Road World Championships — are huge audience draws.

Competitive BMX biking, where cyclists launch themselves into the air to perform seemingly impossible tricks, also has a healthy fanbase. Predominantly a U.S. phenomenon, BMX freestyling was high-profile enough to become an Olympic event in 2020. Also in this adrenaline-filled category is mountain biking, which gained traction in the 1970s and prompted the invention of heavier bikes with robust tires for multi-terrain travel. This cycling pursuit is just as suited for races and competitions of skill and daring as it is for nature lovers seeking a new outlet for their wanderlust.

There is much to be said for the bicycle's simplicity, and its appeal persists in no small part for that very reason. But as we have seen, behind even the most ordinary technology can be a trail of extraordinary genius. Patents are vital IP rights for protecting this inventive process and ensuring that creators are not left spinning their wheels when it comes to capitalizing on their work. That is why the experts at Dennemeyer are always ready to serve your full spectrum of IP needs anywhere.

Filed in

IP infringement disputes abound in the film industry but some are more dramatic than others. Explore the unusual IP cases spawned from prominent movies.