Everyday IP: Inventions and innovations with unpopular debuts

As the son of a patent attorney, cartoonist Bill Watterson was well positioned to wryly comment that genius is never understood in its own time. Though his intention might have been to remark that the difference between brilliance and folly is often a matter of perspective, there is an enduring relevance to the statement, nonetheless.

The truth is that not all groundbreaking inventions are met with enthusiasm or even acceptance. Though just as worthy of their Intellectual Property (IP) rights as any other novel creation, various shades of dismissal, mockery and hostility sometimes color the reception of technologies that time later vindicates. We take a look at the intriguing, surprising and occasionally amusing history of modern necessities that were poorly received upon their debut.

Electricity comes as a shock

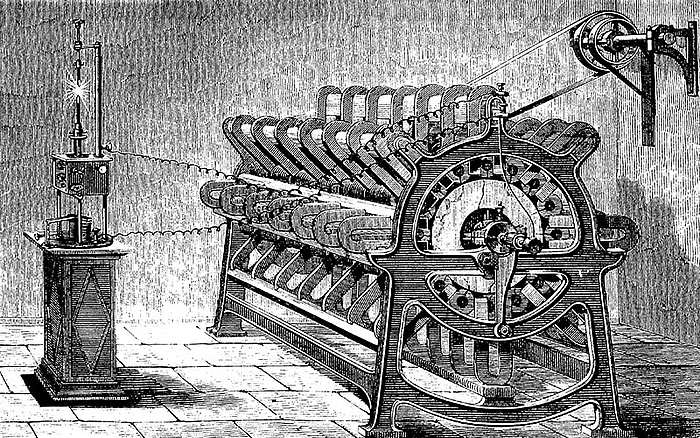

The turn of the 19th century and the decades that followed saw numerous milestones in electrical research: Alessandro Volta's zinc-copper battery, Hans Christian Ørsted's discovery of electromagnetism and Michael Faraday's pioneering work on electric motors and generators, to name just a few. However, the effects and applications of this hazily understood form of energy were largely regarded as curiosities in a period dominated by coal-powered steam engines and gas lighting.

Only in the 1870s and 1880s did inventions like Alexander Graham Bell's telephone and Thomas Edison's phonograph and light bulb wake up the scientific and commercial communities to electricity's potential. Yet the light bulb — which Edison patented, based on earlier concepts — received disdain from various scientists despite the contemporaneous launch of electric lighting systems in major cities, beginning with Cleveland, Ohio, in 1879.

The 1880s and 1890s in electrification were defined by the so-called War of the Currents: alternating current (AC) and direct current (DC). In the end, AC won out for long-distance power transmission due to low energy loss at high voltages. Meanwhile, DC lies at the heart of today's electric vehicle revolution.

Even Edison, the famous holder of 1,093 patents, was not immune to skepticism: As a firm believer in DC transmission, he dismissed his employee Nikola Tesla's work on AC. In the end, the Croatian-born, New York-based prodigy emerged triumphant, as AC is today the primary means of delivering current long distances across residential and commercial grids.

A sputtering start for cars

In Europe, the pioneering work on automobiles of Siegfried Marcus, Carl Benz, Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach (among others) captured the fascination of engineers, designers and entrepreneurs. After Benz received the first patent for a gasoline-powered car in 1886, the stage was set for a revolution in personal transport.

That being said, in the United States — like much of the rest of the world — it was a different story. Charles and Frank Duryea hand-built early cars for the U.S. market around the same time as Benz and his contemporaries, but their inventions (and those of other domestic automobile innovators) were viewed as impractical and dangerous by their countrymen. Cars were then considered a fad, just as bicycles had been.

But before long, Henry Ford's landmark development of assembly-line manufacturing changed world history. The Ford Motor Company's Model T was much cheaper to build than its competitors and thus could be more reasonably priced. As it happened, bicycles also proved their U.S. doubters wrong.

"Talking pictures" and deaf ears

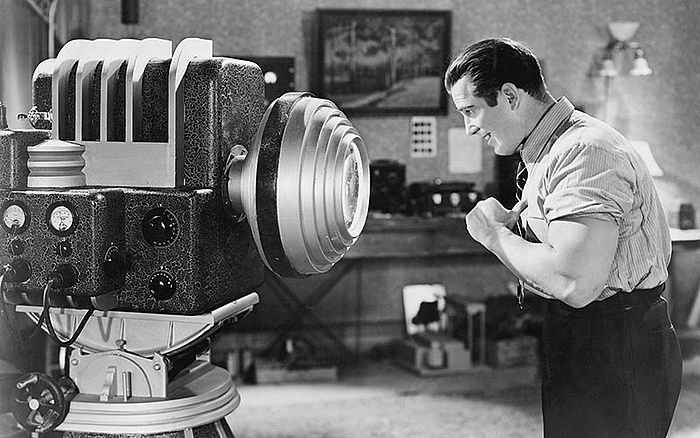

During the earliest years of cinema's mainstream success between the early 1910s and late 1920s, films lacked sound effects and audible dialogue, accompanied instead by live music: usually organ or piano. Film camera technology had advanced well ahead of audio recording, so the absence of sound was simply the reality of the medium. Though this state of affairs was to prove relatively short-lived, when sound technologies did begin to catch up, much of the industry was doubtful of the new "talkies."

Synchronizing images and sound on a single playback medium proved to be a great technological hurdle. Once overcome, filmmakers had to re-think cinematography to make full use of the new dramatic potential, with one of the early beneficiaries being musicals.

Those in the entertainment industry make assumptions of public opinion at their own peril, and when Warner Brothers produced and released "The Jazz Singer" in 1927, it defied these expectations to become a smash hit. A star vehicle for Al Jolson, the film was not the first motion picture with sound effects, but it did feature a synchronized pre-recorded score and, crucially, vocals (mostly Jolson's musical numbers). Various executives, producers, directors, actors and critics — principally in Hollywood — thought (or perhaps hoped) that talkies would be a passing craze. After all, they had already established themselves and did not savor the thought of being uprooted by a new generation of filmmakers and performers. Just like those who held similar beliefs about bicycles and cars before them, the cinema cynics were left on history's cutting-room floor.

Does not (home) compute

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, basic knowledge, or rather awareness, of computers among the general population was on the up and up. By that time, computers were making headway into various industries and were already immensely important to government and academic research. A number of computer pioneers from the era, including Digital Equipment Corporation founder Ken Olsen, believed that consumers would actively disfavor the intrusion of the computer into their private lives.

Since an ill-judged comment at a World Future Society convention in 1977 that there was no "no reason for any individual to have a computer in his home," Olsen repeatedly asserted his remarks were taken out of context. Dogged for years by the prediction, he held that he was referring to living within an entirely computer-controlled environment: a slightly twisted expansion of the so-called "Internet of Things" concept. But Olsen's protestations to one side, a distrust of home computers fomented throughout the 1980s and persisted as late as the 1990s, with some even claiming it was an innate fear.

Today, most people's biggest fear regarding early personal computers would be of breaking a valuable antique. However, in their day, these devices were seen as a genuine threat to many office jobs rather than simply as a tool to enhance productivity.

The fact that personal computers were very expensive, with workings that were totally abstruse to all but the initiated, did little to quell this lingering trepidation. Nor did the apparent threat they posed to the viability of certain professions. These days, a similar sense of alarm surrounds generative AI, though the technology and its effects are still too young to definitively appraise – even regarding their impact on the IP industry.

Hung up on mobile phones

Even Martin Cooper, the Motorola engineer who placed the first in-public call from a handheld mobile phone in 1973, had reservations about the technology. During a 1981 interview — two years before Motorola released the first consumer mobile, the DynaTAC 8000x — Cooper claimed, "Cellular phones will absolutely not replace local wire systems. Even if you project it beyond our lifetimes, it won't be cheap enough."

At the time, this likely sounded realistic to many. Network infrastructure for mobiles was scarce, and the devices themselves were cumbersome, unreliable and unaffordable for most customers. But if anyone could imagine the future of cellular technology, one would think it would be a person instrumental in its development. And yet, Cooper did not, nor did many of his contemporaries in the telecommunications industry.

Of course, the necessary infrastructure was developed much sooner than Cooper had anticipated, and mobiles became more convenient and less costly. By the early 2000s, they were a common sight and just two decades later, it was estimated that more than half the people on the planet owned a smartphone.

Dennemeyer sees the potential in your patents

An invention does not have to be the next big thing to be worth receiving a patent. The time, knowledge and resources you invest in the development process deserve the chance to reap their reward. As an IP full-service provider with a globe-spanning network of experts and agents, Dennemeyer is poised to establish strong patent protection for your innovative efforts.

Filed in

IP infringement disputes abound in the film industry but some are more dramatic than others. Explore the unusual IP cases spawned from prominent movies.